Here it is in PyCon US 2023

Slow tests are not fun.

In this post, I’ll talk about two ways in which they are not fun

- The bottleneck and the time bomb

- The feedback loop and the bug funnel

The bottleneck and the time bomb

The bottleneck here is where the tests take so long to run, that we have a long queue of tasks waiting to be merged to the main branch.

(this assumes we’re merging tasks to the main branch one-by-one, and only after the tests pass. Other branching models have similar issues, but this is the simplest to explain)

When the tests take too long to run, the merge queue becomes long.

How slow is too slow?

Assume we have, say, 10 work-hours each day.

5-minute test suite

If the test suite takes 5 minutes to run:

That’s 12 merges per hour, or 120 merges a day, before the tests slow us down.

For most teams, that virtually never happens, so a 5-minute test suite is not a bottleneck.

2-hour test suite

On the other extreme, and it usually won’t get to that but just so it’s easy to imagine -

If the test suite takes 2 hours:

That’s only 5 merges per day.

And that’s the best-case scenario: if nobody ever makes a mistake and the tests always pass and the next dev starts running the tests immediately after the previous one finishes.

In a case like that, whenever we want to wrap up a bunch of tasks quickly, maybe before a major version, the merge queue length becomes days.

And if people sometimes make mistakes and the tests fail or some manual test takes a bit longer, then we might not be able to even merge 3-4 tasks in a normal day.

It just doesn’t work.

The team will probably just stop waiting for the tests to pass before merging, and spend a lot of time with the tests being broken.

Now, we can SURVIVE this way.

But it’s a lot of extra work and it’s really not what we want.

Where’s the line?

Really, this happens with numbers that are far less extreme.

In my experience, with a 30 minutes test suite the same things happen.

Less frequently, but still.

I would say a good rule of thumb is to aspire to 10 minutes, and never accept more than 20.

That time when the bomb exploded

A few years ago I was actually part of a team where this happened.

When the tests took 20 minutes, I understood it’s a time bomb and eventually things were going to get bad.

But I didn’t have this clear phrasing of exactly how the slowness would be a problem. The bottleneck.

Granted, at that team we had other problems as well:

- The tests were a little flaky - sometimes failing randomly.

- The tests were difficult to debug - to understand why they failed

- The tests were brittle - small unrelated changes might make them fail (this is different from flakiness, which is random failures).

This combo made it so that there was always some failing test that needed urgent fixing, which was “something we could chase”.

These urgent fixes masked the slowness problem, because it always seemed like “oh, ok, we just need to stabilize this thing and then it would be ok”.

After a while, we were getting all these problems every few weeks.

Multi-day merge queues, everything was stuck.

Real crisis mode.

It only became ok after we did an expensive project and made the tests run in parallel.

Tests would still break sometimes, but the queue got back to zero fast enough so it was not a crisis.

What can we do? Make the tests isolated

The question is - what do we do about this?

Meaning, we’re starting a new project (or have an existing project which is not in crisis mode) - what actions should we take to prevent this from happening in the long run?

We don’t want premature optimization, so what we need on day 1 is to make sure that WHEN we want to optimize, it’s not going to be a very expensive project.

And specifically, it should be possible to run the tests in parallel because that’s going to be the go-to solution.

The only thing we need for that, is to remember the footgun about isolated tests. If the tests don’t affect each other, they can run in parallel, and then the chances of a horrible crisis become much lower.

So my advice is to consider test isolation as a must-have.

The feedback loop and the bug funnel

Another way that slow tests can hurt us is by making our feedback loop longer.

The feedback loop is how fast we learn about bugs and understand what happened.

And I’m talking about any type of bug here - anything from a typo to complex concurrency issues.

The feedback loop is very important, and anything that makes it shorter is effective.

Even a squiggly red line in the IDE.

I usually aim for a setup where most of the time, I’m working in watch-mode, so the tests re-run every time a file changes, and I run a sub-set of the tests that finishes within 2 or 3 seconds.

Note: This watch-mode setup is for when I'm coding manually.With AI agents, the feedback loop takes a different form, where the AI agent itself should have a feedback loop of its own, but that's a different topic.

I'm also writing (A LOT) about that. See my post series about AI-first design patterns and frameworks

Being fast is easy for the brain

Being on the fast side is great.

For example, if a test fails just a few seconds after I wrote the code - I instantly understand what’s going on.

I never got out of context - this code has just been created.

However, with a 10-minute tests suite in CI - the commit with a failing test often contains a lot of code.

Plus my brain will do a context switch and go catch up on slack.

So when I try to understand what’s going on with the failing test - it’s a lot more work.

But some tests HAVE to be slow, right?

True. For many projects, the reality is that some tests are going to be slow, no matter what we do.

But it doesn’t mean hope is lost - we can still have pretty fast feedback loop.

How?

What helps me here is that instead of asking

“How long does it take for the tests to run”

I’m asking

“How long does it take to catch a bug”

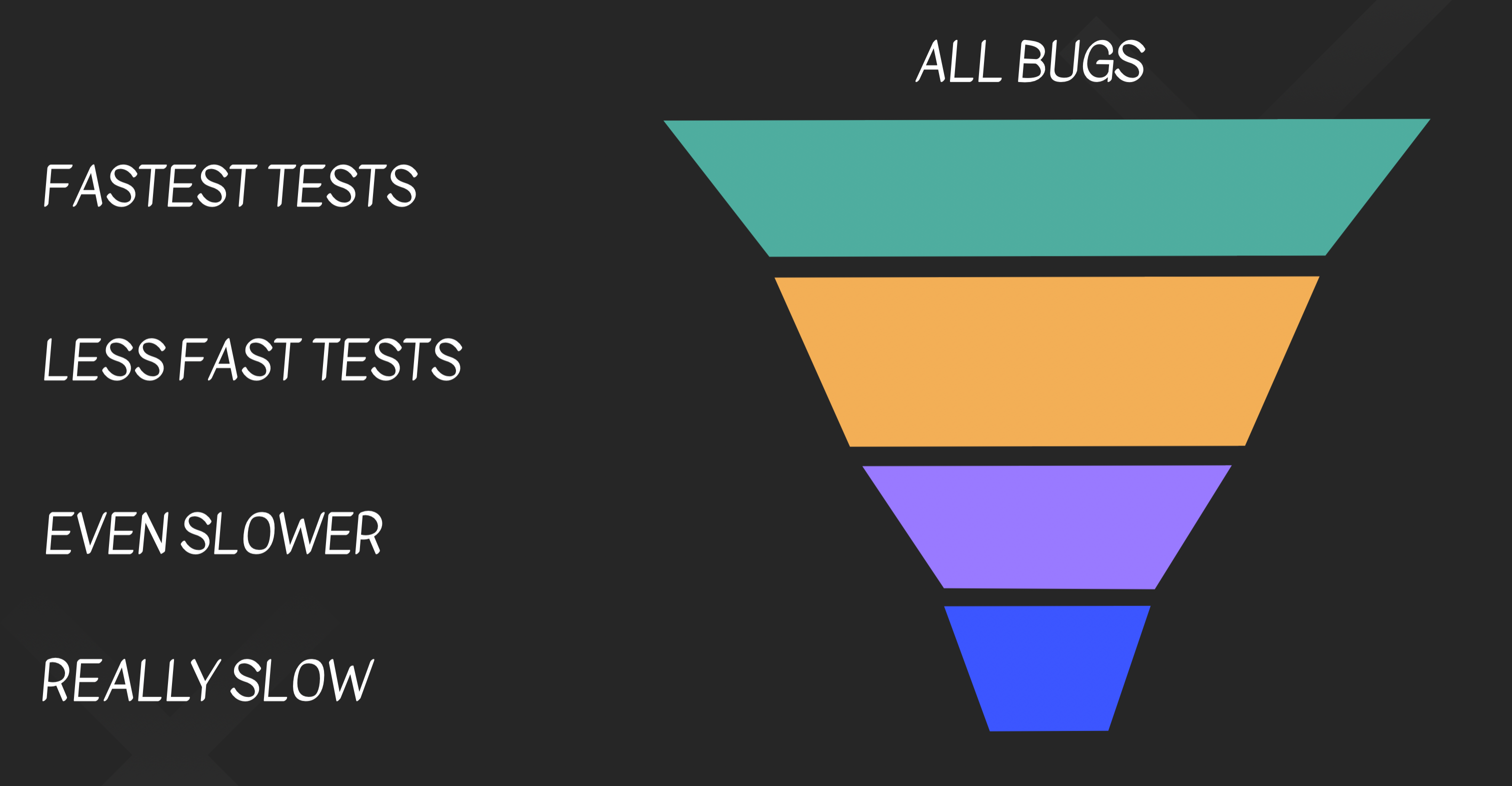

And I’m visualizing this using the “bug funnel”.

All possible theoretical bugs come in, and some of them get filtered out on every stage.

And the key observation here is that we don’t need to catch ALL bugs quickly:

- We need to catch MOST bugs quickly.

- The feedback loop needs to be USUALLY fast.

To understand why, we’ll look at an example.

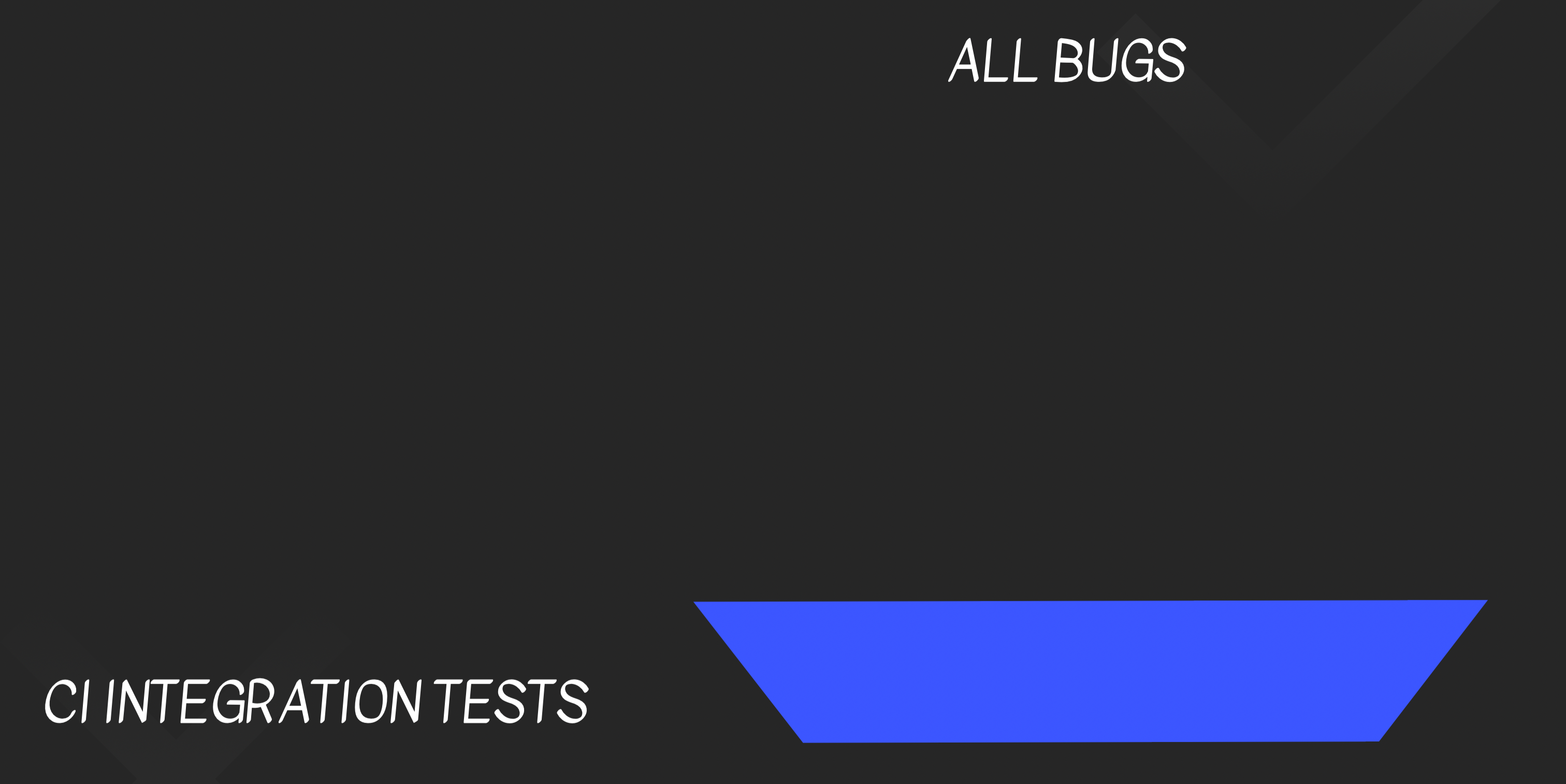

Assume we start out with a bug funnel that looks like this:

We only have long-running integration tests, and we only run them in CI.

Let’s say that during the work on some task, we create 10 bugs.

This means that 10 times, we’ll discover that we have a bug only after we commit, push and wait for the CI to run the

tests.

And in all 10 times, our debugging is also going to be more difficult because of context switches etc.

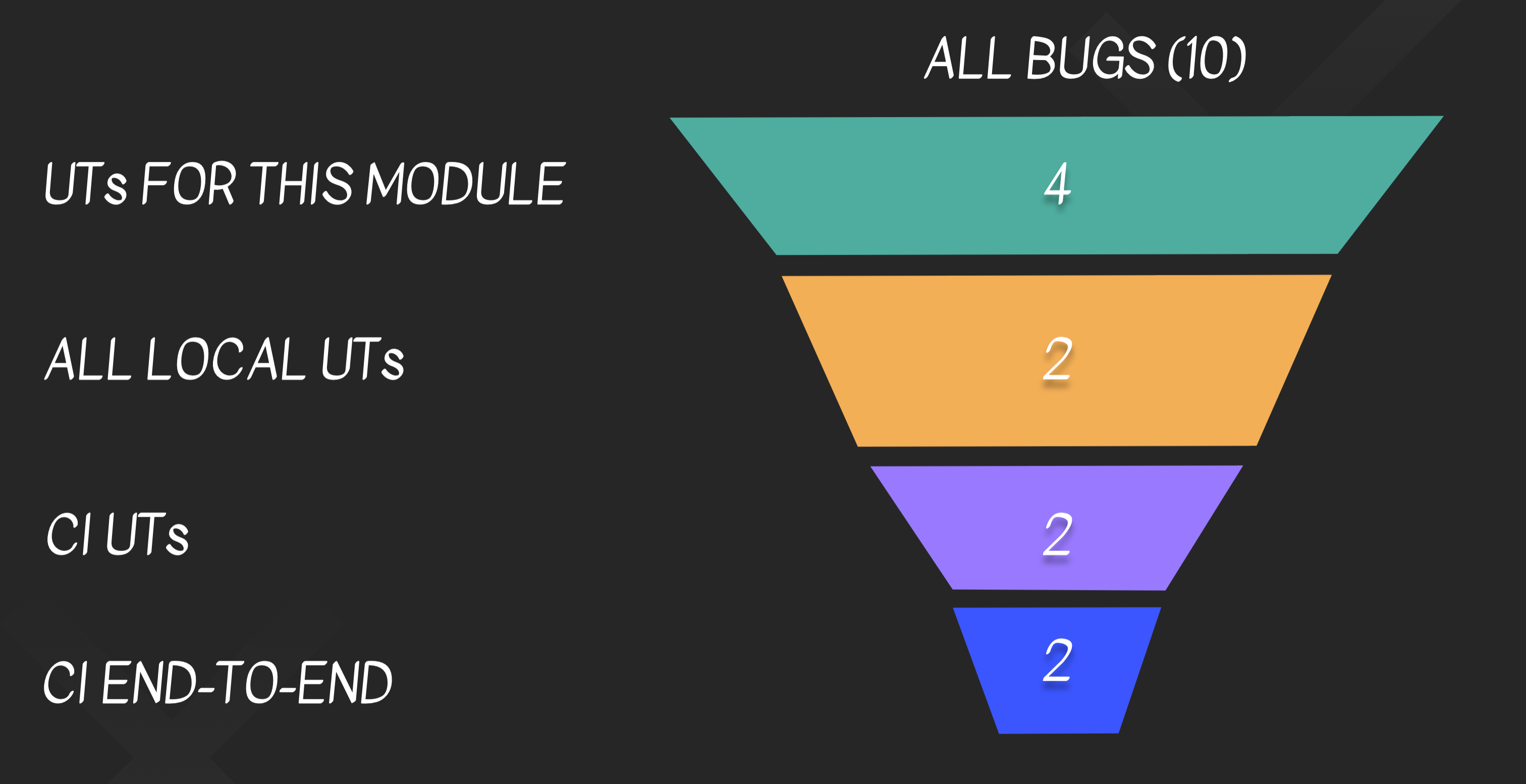

But what if we add some faster tests?

Let’s say that, instead, we have this:

For the same task with the same 10 bugs - we won’t wait 10 times for the long-running CI. Only for, say, 2 of the bugs.

For the rest of the bugs, so most of the time - we’ll have a much faster feedback loop because they would be caught by

a faster test.

Note that we’re still getting the value even if the UTs don’t catch any bug that the integration tests wouldn’t also

catch.

So while on first thought you might think that the fast unit tests have a bad ROI because they won’t catch more bugs -

the reality is different.

And don’t forget:

- Try to run at least some of the tests in watch-mode! You will have a 2-second feedback loop, even if it’s not for everything.

- As we discussed - you can also use test doubles, that’s why they exist.

Conclusion

Pay attention to test speed.

The CI can’t be too slow, or it becomes a bottleneck.

Always make tests isolated to avoid a crisis that can hurt the company.

And try to optimize your feedback loop, even if it only works for a subset of your work.