One of the best ways to help our AI agent work on our code is to set it up with a solid feedback

loop so it can “plan -> do -> verify” on its own.

We define the design, and the agent follows our conventions to create code and tests that enable the feedback loop.

(that’s the premise of this post; earlier posts in the series go deeper on the rationale).

Turns out that if our code is a backend API service, there are simple design and testing patterns that have

a great ROI.

We don’t need to invent anything new; there are well-known, established options. We just need to pick

ones that are a good fit for creating an AI-internal feedback loop.

This post looks at two classic approaches that work well.

You probably already know them, but to make them effective for an agent we need to make some specific implementation

choices.

We’ll walk through those choices, explain why they work when others don’t, and dive into concrete low-level details to

help with implementation.

After covering the patterns, we’ll look at an example CRUD backend that applies them and close with takeaways from building the service.

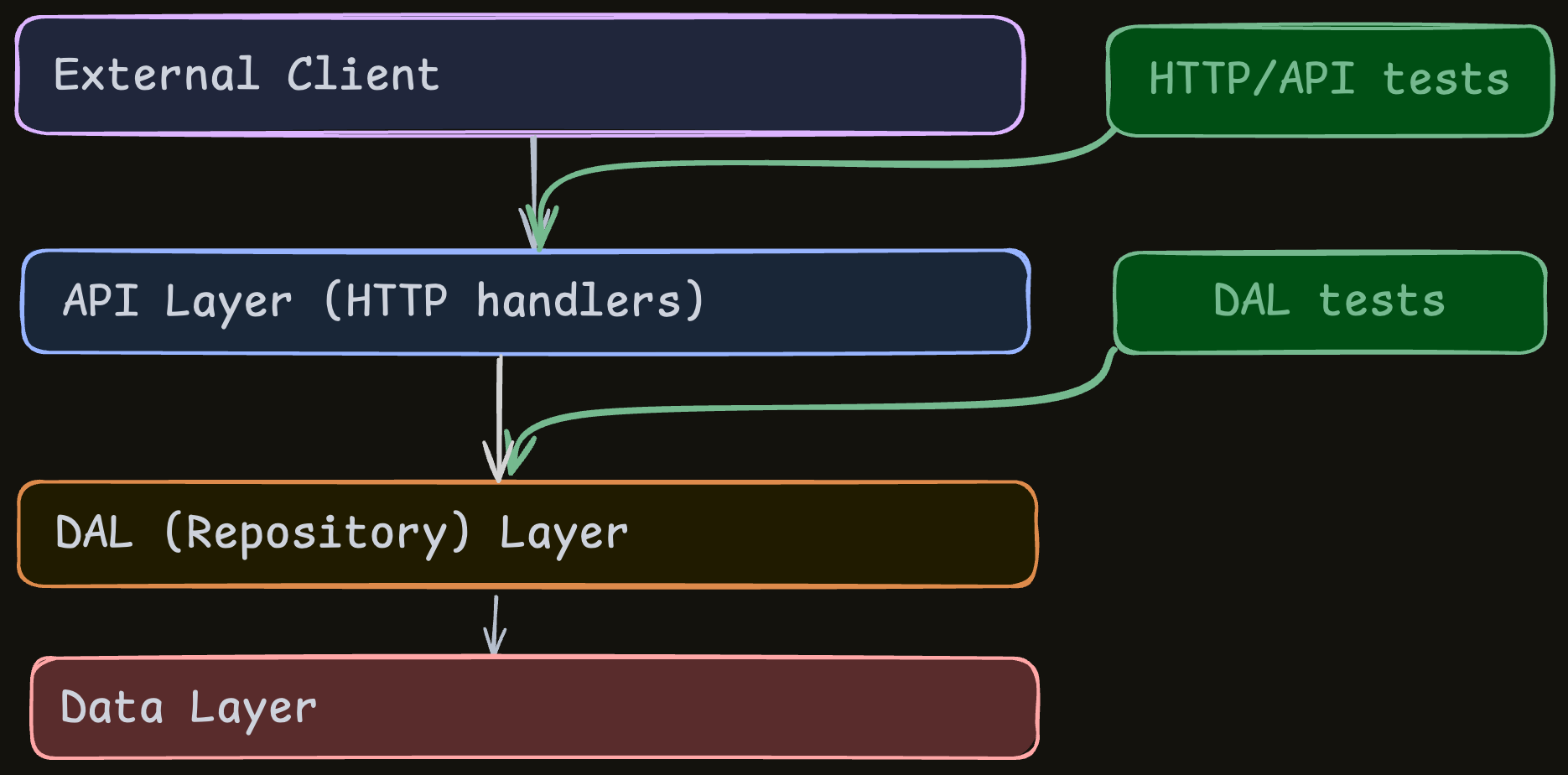

At high level

For those who already speak testing lingo and just want the headline, here’s the short, unexplained list of the patterns and the key choices that make them effective:

Design pattern #1: Rely heavily on HTTP API tests. Use them to cover as much functionality as possible. Key choices:

- API-level really means API-level: everything goes through HTTP, including test-data setup.

- Make the DB fast enough for tests (in-memory, fakes, local DB etc.), even if it takes effort.

- Use an in-process TestClient if possible.

Design pattern #2: Also have a DAL and test it thoroughly (optional but strongly recommended). Key choices:

- DAL-level means DAL-level: interact only through the DAL interface, including test-data setup.

- Use the same DB considerations as with the API tests.

This post focuses on a local CRUD backend service.

The covered patterns can be thought of as “fundamentals for a backend service”; they form the base that we can build on.

Other concerns, like external dependencies, are obviously important but we can only cover so much in one post so they’ll

have to wait their turn.

What’s the basic goal?

To make the feedback loop effective, the agent needs to check itself.

For that to work, the tests must be “good” in specific ways:

- Close enough to the truth: pass/fail should usually mean no-bug/bug.

- Extensive enough: broad coverage of the service’s behavior.

- Fast enough: runnable after small code changes.

Notice that each point contains “enough”.

It has to be good, but it doesn’t need to be perfect; if the agent catches most bugs quickly, that’s already a 10x boost.

How is this different from normal testing?

On one hand, it’s not very different - these same considerations are important in normal testing as well.

But agents make them more important, because getting the tests right can be the difference between the agent having a decent feedback loop and not having it.

The agent relies on the tests for its quick feedback.

If they’re unreliable, not extensive, or too slow to run after small changes, the agent won’t get the

feedback it needs. It’ll go off in the wrong direction without any way to notice, and a lot of the verification work

will fall back on us humans, which defeats the purpose.

Agents also shift the tradeoffs.

Writing code and tests is much cheaper now; we can have a thousand where we earlier had ten.

The hard part is making sure they exercise something real, so investing in a setup that biases tests toward quality now

has a much higher ROI.

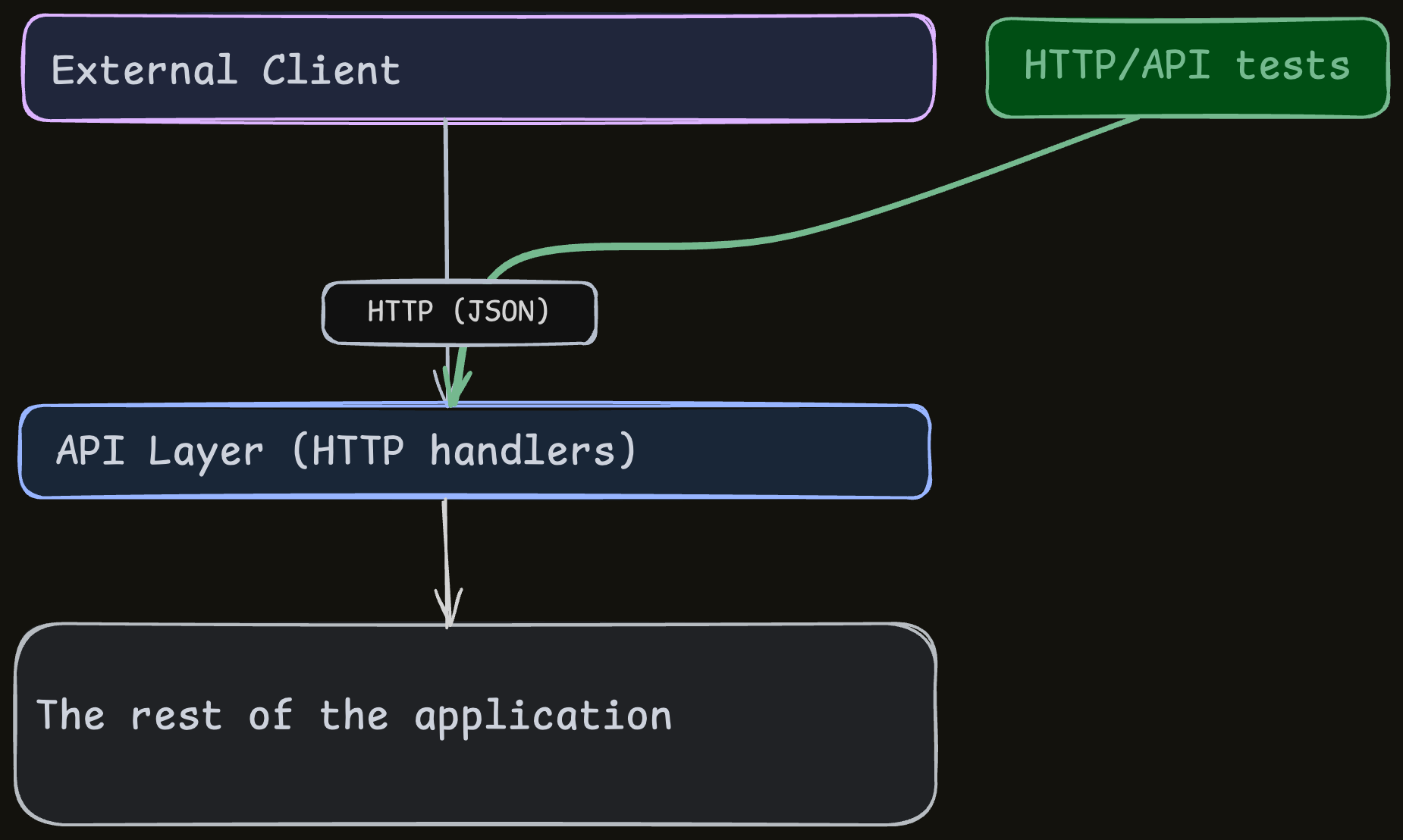

Design pattern #1: Heavily rely on API tests

This is the most important (and most obvious) idea.

It works with any code design, as long as you have a way to handle the DB.

The “truth” about how an API service behaves is its HTTP interface.

If it receives HTTP requests and returns the right responses, it works.

So obviously, this is the most reliable way to test it: tests that interact with the service as if they are an external

client.

This means that in many cases, the default strategy for testing a service is to lean on API tests:

- Build a solid setup for the API tests.

- Have the agent write thorough tests for all possible functionality through these API tests.

It won’t cover everything, but if this is the starting point, you’re already in a strong place.

The tricky part is building a solid setup for the tests.

There are many ways to write API tests, and we need to pick the ones that avoid the pitfalls

that would undermine the feedback loop.

Performance pitfalls

The best option is to have the API tests run as in-process unit-tests, with the DB being in-memory.

How can HTTP API tests be in-process?

Many web frameworks have a “TestClient” that allows simulating HTTP requests.

You get the exact same interface as a real HTTP client, and the framework sets it up to be functionally identical

(or close-enough).

Example (Python - FastAPI + pytest):

def test_create_user_as_super_admin(self, client: TestClient) -> None:

response = client.post(

"/api/users",

params={"organization_id": org_id, "role": "admin"},

json={"username": "newuser", "email": "new@example.com", "full_name": "New User"},

headers=auth_headers(super_admin_token),

)

assert response.status_code == 201

...

The Pythonists among you may notice that client.post looks exactly like the popular requests.post function.

So we stay within the same process and use simple function calls instead of having a separate process with an actual

HTTP server.

Very fast and still reliable-enough.

What about the DB?

The thing we have to have for the feedback loop is “the tests must be fast-enough and reliable-enough most of the

time”.

So yes - it’s a non-trivial challenge, but there’s a lot of wiggle room.

Here are some options on the DB front:

- In-memory mode: use it if your DB supports it.

- Use a fake DB: a fake is a simulator that behaves like the real thing for tests. For example, an in-memory DB (e.g. SQLite) might stand in for Postgres with a small adapter.

- Set up your DB so it’s local and fast enough.

- Add utilities that keep the DB fast:

- E.g. for local Postgres, bake everything, including test data, into a docker image and spin up a fresh container per test suite for a clean, instant DB.

- Explore caching, pre-calculation, parallelization, etc.

- Set up the agent so most of the time, it only runs a small subset of the tests that are related to the changed code.

- Fake the DAL: if the other solutions don’t cut it, then your only option might be to use a DAL (Data Access Layer - which is a good idea anyway, see below) and create an alternative DAL implementation that doesn’t use your DB. For example, it can use simple data structures that behave like the DB in tests. It takes more work (mostly for the agent) and is less reliable, but if that’s the only option, then that’s life.

- Keep both a “fast mode” (e.g. in-memory SQLite) and a “reliable mode” (real Postgres), and run the reliable mode only occasionally.

The core idea is to be pragmatic: be good enough most of the time.

That’s enough for a decent feedback loop.

Correctness pitfalls

These points are true in any testing effort, but agents amplify them.

Correctness is tricky because plenty of popular “best practices” just won’t work here.

Because the only real dependency in a CRUD is the DB, the main correctness issue is how we create and access the thing that lives in the DB: the test data.

The right thing to do is to create and access test data through the interface you’re exercising.

For API tests, behave exactly like an external client:

- Generate all test data through the layer that we’re testing - in this case the HTTP interface itself.

- Verify the results - again, though the same interface.

Don’t use the ORM, the DAL, mocks, stubs, or any other internal shortcut.

If you do, the data can drift from reality and the tests become unreliable.

Subtle bugs creep in; for example, asserting on a raw DB value that the system uses in a different way than expected.

Because the agent relies almost completely on these tests for feedback, it has no way to notice it’s creating bugs.

Make the effort; it’s the best investment you can make.

If you’d like a more concrete look, I mentioned this at a PyCon US talk (in a non-AI context, but everything still applies), and following that talk wrote a blog post about it.

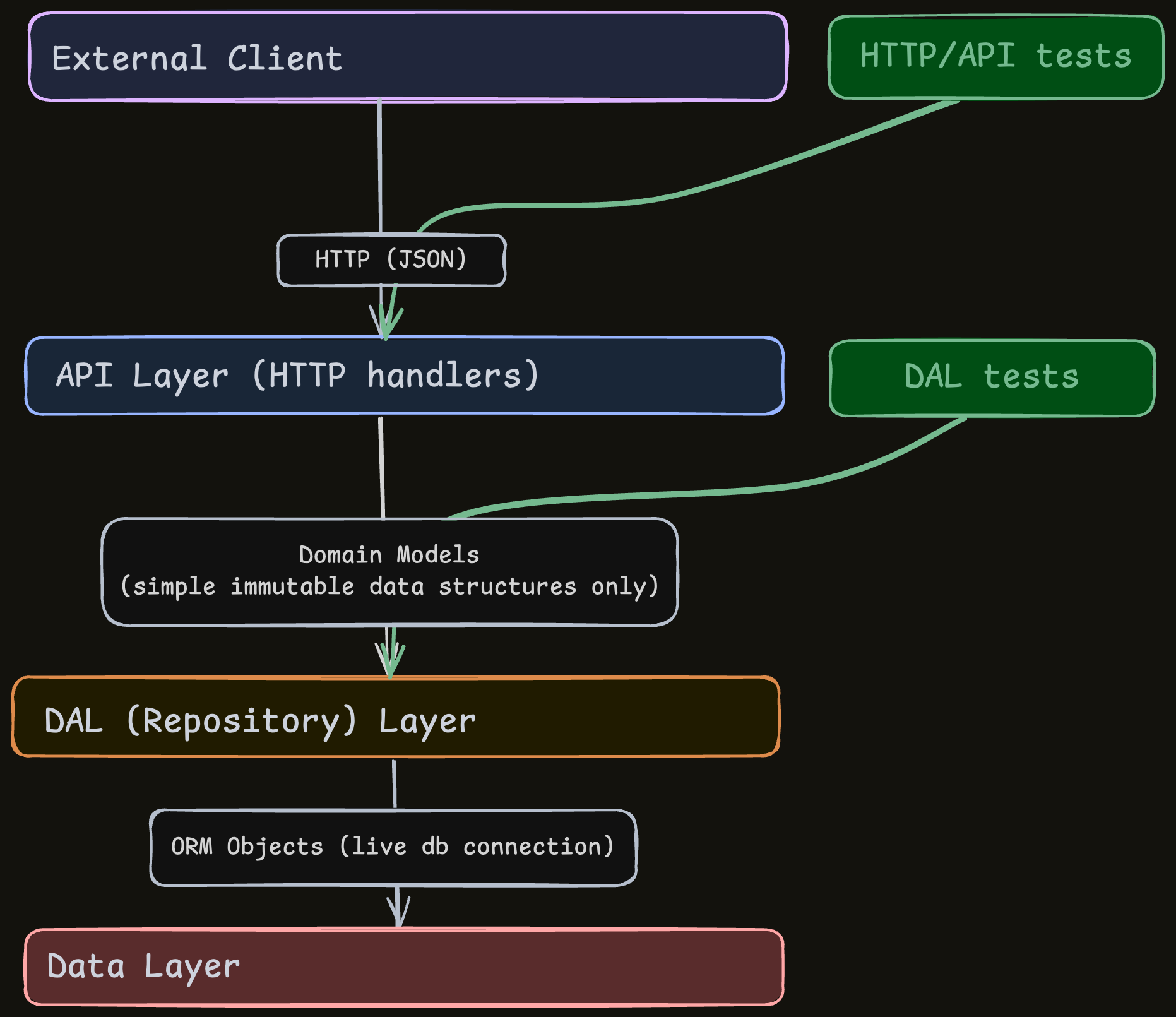

Design pattern #2: Have a DAL with its own strong tests

What’s a DAL?

A common pattern when working with DBs is to add a DAL (Data Access Layer, sometimes called a repository) that abstracts and encapsulates DB access.

The DAL exposes a small set of actions against the DB, and the rest of the service only uses those actions.

They take and return domain-model objects (immutable data structures representing entities like User, Project, Ticket).

Code outside the DAL doesn’t have access to the DB or the ORM. It only knows the domain-model objects and the DAL handles

the DB itself.

For example, creating a User might look like this:

def update_user(

self,

user_id: str,

update_command: UserUpdateCommand, # INPUT - simple data structure, not connected to DB

) -> Optional[User]:

# DB ACCESS is here:

orm_user = self.session.query(UserORM).filter(UserORM.id == user_id).first()

# ...

# Where the UserUpdateCommand is just a data structure:

class UserUpdateCommand(BaseModel):

email: Optional[EmailStr] = Field(None, description="User email address")

full_name: Optional[str] = Field(None, min_length=1, max_length=255, description="User full name")

role: Optional[UserRole] = Field(None, description="User role")

is_active: Optional[bool] = Field(None, description="Whether user is active")

Why have a DAL + tests?

A DAL has downsides (like code bloat).

We still want it because it gives the agent a consistent way to make the code more robust:

- It’s possible for the agent to work on it effectively: we can set up a feedback loop around a DAL because it can be tested on its own.

- The API tests by themselves might not be enough, and strong DAL tests add reliability around the DB access, which is typically one of the most error-prone areas.

- Design-wise, this encapsulation usually improves maintainability.

Two more subtle benefits:

- Clearer context makes it easier for the agent to focus:

- Outside the DAL, the only DB context the agent needs is the narrow DAL interface. Without a DAL, DB access spreads across many files and patterns, making it harder to surface the relevant details.

- Inside the DAL, the agent mostly needs the rest of the interface plus the DB logic contained within the DAL.

- Protect the feedback loop from future disasters:

- As mentioned above, if you don’t have a fast-enough DB setup, you might be forced to have a DAL and create a fake (simulator) for it.

- BUT, even if you do have a fast DB setup TODAY - in 6 months you might need to change the DB for some of your data for scale reasons. And the new DB might not have a fast-enough setup.

- So if you don’t start with a DAL today, you will be forced to create a new DAL and a fake for it or say goodbye to your agent’s feedback loop.

- But by then, you might have thousands of lines of code that access the DB directly, and you’ll need to refactor all that sensitive code into the new DAL - which might be very expensive and introduce bugs.

- Don’t risk it.

What choices do we need to make for the DAL tests?

So we want to have a DAL, and we want to have our agent write thorough tests for it.

The setup is similar to the API tests, so the same pitfalls apply:

- Run everything through the DAL’s external interface (the repository API that uses domain models), not the ORM or other internal APIs.

- Keep the tests fast; the DB considerations are similar to the API test setup.

Summing up our patterns

Because API-level tests are the “truth”, a fast and reliable DB setup makes them enough to give the agent a solid

feedback loop.

In my recent experience, this works so well that I wouldn’t start a new service without them.

For a small CRUD, API tests might be sufficient, but I still recommend adding a DAL with thorough tests.

Yes, it’s more code, another abstraction, and some overlap, but the agent handles it fine (often better, thanks to

clearer context) and the system ends up sturdier and easier to maintain.

Example project

To make this concrete, I

created a small-ish CRUD backend

project

that applies the design patterns above.

If you’d like to see them in practice, browse the code (links to specific files below).

It’s a Python backend for a basic project management app with:

- Organizations (tenants) with isolated data

- Role-based access control (Admin, Project Manager, Write Access, Read Access)

- Projects containing tickets with configurable workflows

- Epics that span multiple projects

- Comments on tickets

- Activity logs and audit trails with permission-based access

There’s a rough UI covering part of the functionality. It’s not part of the workflow I’m describing; I just created it to get a feel that the API is usable:

Project structure

This project was created pretty much entirely by an AI agent (Claude Code, with guidance of course) - I set up scaffolding and agent rules for coding conventions and the feedback loop, and the rest was generated by the agent in several sessions.

The stack uses common Python tools such as FastAPI and SQLAlchemy.

It’s a local-only SQLite setup with a few thousand lines of code, enough to show the design on something richer than

“Hello, World”.

The structure mirrors what we’ve discussed. Examples:

- One of the API routers: https://github.com/shaigeva/project_management_crud_example/blob/main/project_management_crud_example/routers/ticket_api.py

- DAL: https://github.com/shaigeva/project_management_crud_example/blob/main/project_management_crud_example/dal/sqlite/repository.py

- Tests:

- One of the API tests: https://github.com/shaigeva/project_management_crud_example/blob/main/tests/api/test_ticket_api.py

- One of the DAL tests: https://github.com/shaigeva/project_management_crud_example/blob/main/tests/dal/test_ticket_repository.py

- In addition to the API and DAL tests, there are some unit tests for specific modules, in cases that a module can be tested in isolation without mocks etc.

Tests: some extra details

Spinning up a fresh DB is quick here, so each test gets a new physical SQLite file in a temp directory. We seed it with test data and discard it when the test finishes.

The full suite takes ~20 seconds.

That’s fine for an example, but in a larger project I’d default to in-memory runs, cache more of the setup, and have the

agent run only the tests related to the change so typical runs stay in the several-second range.

Honorary mention: Spec-driven development

The focus of this post is on code & tests design, so I won’t get into the details here, but it’s worth a mention that

workflow-wise, the project is spec-driven in spirit.

It follows a ~consistent pattern to move from high-level spec to low-level implementation, and this has been a major part

in getting the agent to do consistent, focused work.

┌──────────────────────────────────┐

│ High-Level Spec │ (main features)

└────────────────┬─────────────────┘

│

▼

┌──────────────────────────────────┐

│ Detailed Specs │ (persistent - requirements & acceptance

└────────────────┬─────────────────┘ criteria for specific features)

│

▼

┌──────────────────────────────────┐

│ Current Feature Implementation │ (ephemeral - archived when done)

│ Plan │

└────────────────┬─────────────────┘

│

▼

┌──────────────────────────────────┐

│ Code and Tests │

└──────────────────────────────────┘

Summing up

My goal with this post was to highlight foundational design and testing patterns for API services and show why they are better than others for AI-first development.

I shared the details to keep things concrete enough to try.

In my experiments, these patterns perform very well, and I hope

they’re useful to you, too.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on social (twitter / x, linkedin)!